Wager

The wages of Wager were famine, pestilence, destruction and death.

Note: I double-checked my English major math, and it seems to be true. I recently survived my 81st birthday. Some days I feel 16; other days 116. One thing is sure: I’m slowing down. I have not written a substack for a while. I’m conflicted. I miss writing fiction and would like to write another novel. On the other hand, I don’t want to give up substack. I arrived here fairly early, before the big kids came along. It would certainly be no loss to the world were I to stop writing my substack. I am afraid it would be a loss to me, however. Writing has become both a passion and a distraction in old age. Writing is excellent brain exercise, and I find that as I get older, I am living more and more inside my head.

The War of Jenkins’ Ear

A friend gave me the book The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder. I had not heard of the book and began reading it without realizing it was a #1 NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER. I soon realized why. The book is a compelling read.

Wager was the name of a wooden sailing ship of the British Royal Navy. Originally built around 1734 as an armed trader for the East India Company, she was converted to a warship in 1739 after purchase by the British Admiralty.

At war with Spain (War of Jenkins’ Ear), Wager was assigned to a squadron led by Commodore George Anson. Her mission, sponsored by First Lord of the Admiralty, Admiral Sir Charles Wager, after whom the ship was named, was to disrupt Spanish naval operations and economic ventures in the Pacific and in the Spanish colonies on the west coast of South America. From the book:

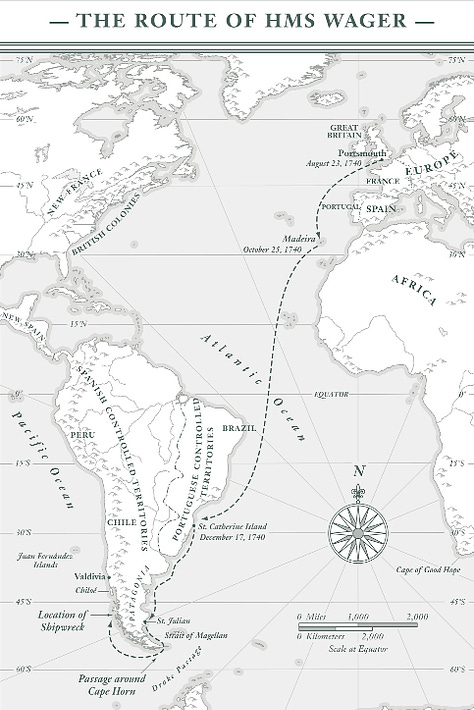

With five warships and a scouting sloop, he (Anson) and some two thousand men would sail across the Atlantic and round Cape Horn, “taking, sinking, burning, or otherwise destroying” enemy ships and weakening Spanish holdings from the Pacific coast of South America to the Philippines. The British government, in concocting its scheme, wanted to avoid the impression that it was merely sponsoring piracy. Yet the heart of the plan called for an act of outright thievery: to snatch a Spanish galleon loaded with virgin silver and hundreds of thousands of silver coins. Twice a year, Spain sent such a galleon—it was not always the same ship—from Mexico to the Philippines to purchase silks and spices and other Asian commodities, which, in turn, were sold in Europe and the Americas. These exchanges provided crucial links in Spain’s global trading empire.

The mission was plagued from the start by an unusually cold winter that delayed construction work on Wager and strong unfavorable winds that delayed their setting sail from Portsmouth. Wager finally weighed anchor on September 18, 1740. By the time she reached Cape Horn the crew had already suffered through terrible storms, scurvy and other maladies.

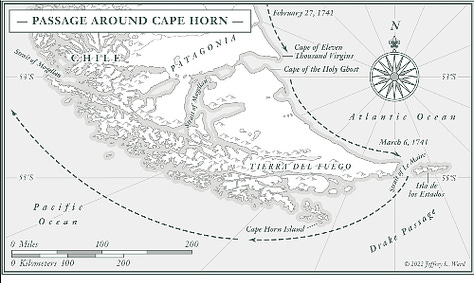

The seas around Cape Horn are reputedly some of the roughest and most dangerous in the world, and the Cape lived up to its reputation to the chagrin of Captain David Cheap and the crew of Wager. The ship spent weeks trying to penetrate the storm within a storm, turn the corner of Cape Horn and head north toward the Juan Fernandez Islands, about 400 miles west of Santiago, Chile.

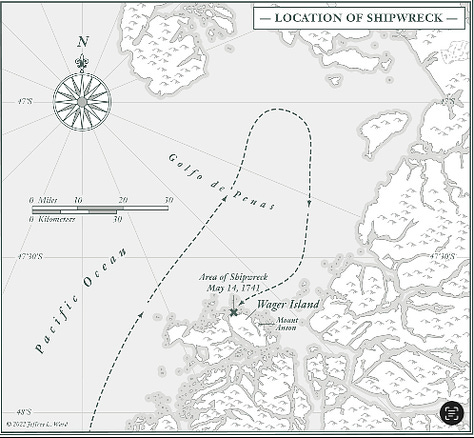

Wager eventually made it around Cape Horn, but by May of 1741 the crew found themselves in El Golfo de Penas (The Gulf of Pain), unable to round another cape, the Cabo Tres Montes (Cape of Three Mountains). This time their crippled ship and much reduced crew (by deaths from scurvy, typhoid, gangrene and frostbite) did not succeed in rounding the cape. Strong winds and currents dashed the ship against the rocky shore of a desolate island that today is named Wager Island after the ship that disintegrated there.

Approximately 140 of the original crew of about 250 made it ashore. The castaways faced terrible conditions on the desolate island that had little vegetation, no game and scant bird life. Captain Cheap tried to maintain the chain of command, but factions formed among the men, and mutiny, a capital crime, ensued. Miraculously, eighteen men of those originally stranded on the island eventually made their way back to England.

That is where a yearslong political struggle ensued over the real story of the tragedy and who was to blame for the mutiny. The events reminded me of the battles over narratives today. I asked Grok to summarize the similarities.

While the book itself is not explicitly about modern American politics, its themes and dynamics resonate strongly with contemporary political issues in the United States as of March 8, 2025. Below are some key similarities that can be drawn between the events and ideas in "The Wager" and the current state of American politics, based on the book’s themes and broader interpretations:

Polarization and Competing Narratives…

Breakdown of Authority and Trust…

Struggle for Power in Chaos…

(Reminds of Rahm Emanuel, then Barack Obama's Chief of Staff’s comment, "You never want a serious crisis to go to waste.")Manipulation of Truth for Political Gain…

The Fragility of Social Order...

Imperial Ambition vs. Reality…

Particularly striking to me were the competing narratives that emerged in regard to what happened to the Wager and its crew and the efforts by the ruling classes to control the narrative and suppress the story. John Bulkeley, the Wager’s gunner, was the only crew member who kept a contemporaneous journal. He was also the leader of the faction that mutinied, deposing Captain David Cheap.

Now, back in England, Bulkeley decided he wanted to publish his journal, taking advantage of the enormous public interest in the ill-fated voyage of Wager and the mutiny that followed her sinking. From The Wager:

The story—or stories—of the expedition continued to capture the public imagination. The press had grown exponentially, fueled by the loosening of government censorship and by wider literacy. And to satisfy the public’s insatiable thirst for news, there had emerged a professional class of scribblers who earned a living from sales rather than from aristocratic patronage, and whom the old literary establishment derided as “Grub Street hacks.” (Grub Street had been part of a poor area in London with doss-houses and brothels and fly-by-night publishing ventures.) And Grub Street, sniffing a good story, now seized on the so-called affair of the Wager.

Bulkeley’s effort to publish led to a firestorm of protest. Elites in the Navy, government and publishing fought viciously to prevent publication of his journal.

It was not unlike the Biden administration, Democrats, Deep State and mainstream media efforts to censor independent media in regard to their exposing their chicanery in trying to prevent Trump from running again for office in 2024. As elites today denigrate independent media as untrustworthy, unprofessional and amateurish, the privileged classes in England at the time did everything they could to thwart Bulkeley and the Grub Street hacks.

In 2004, Jonathan Klein, who was then CNN’s president, said in an interview with The New York Times, “Bloggers have no checks and balances. [It’s] a guy sitting in his living room in his pajamas writing what he thinks.”

He made the remark during the Rathergate scandal when bloggers were responsible for outing Dan Rather and his misreporting of George W. Bush’s military service record. The pajamas image became a disparaging metaphor for independent media scribes. The term became widely used by mainstream media as shorthand in being dismissive of their upstart competition.

Just as during the George Floyd riots viewers were asked to ignore the burning buildings in the background as a reporter described mostly peaceful protests, so did elites of Bulkeley’s time ask the literate to ignore Bulkeley’s eyewitness account of the Wager story in favor of official accounts of the Admiralty written by men who were not at the scene of the alleged crimes.

Some members of the Admiralty and aristocracy expressed outrage at what they considered a two-pronged attack by a gunner and a carpenter on their commanding officer: first they had tied up Cheap, and now they were impugning him in print. One of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty told Bulkeley, “How dare you presume to touch a gentleman’s character in so public a manner?” A naval officer told the popular weekly journal Universal Spectator, “We are ready enough likewise to blame the crew of the Wager, and defend the Captain….We are even apt to think that if Captain Cheap comes home he will remove the censure that has been thrown upon his own obstinacy, and fix it upon the disobedience of those under him.” Bulkeley acknowledged that his defiant act of publishing the journal had in some quarters only fueled calls for his execution.

Thus, the current battle over freedom of speech that seems to many unprecedented is really as old as human nature. Any leader who has sought to control the general population has made every effort to control the dissemination of information. Conversely, anyone who values freedom in general must value freedom of speech above all.

Never stop writing Ross. People like myself thrive on your cogent thoughts. Happy Birthday my friend.

Scott Randle

I recently read "The Wager" and enjoyed it immensely, as I did your essay. While it is fair to say that there are many themes that resonate with current American political trends, I think each of the ones you identify have resonated with current political trends since the dawn of man.