Error Chain Part One

First Link

The first link in the error chain that led to the fatal crash of TWA Flight 514 (IND-CMH-DCA) occurred in 1967. From my book Error Chain: the Bitter End:

The first link went back to 1967 when the U.S. Air Force (USAF) “questioned the FAA’s (Federal Aviation Administration) procedures for instrument approaches with regard to the responsibility for terrain clearance.” In 1970, TAA (Air Transport Association of America) had asked the FAA for clarification of essentially the same issue. In December of that year the FAA issued a General Notice (GENOT) that was designed to clarify the responsibilities of pilots and controllers in maintaining a safe altitude.

In June of 1971, the GENOT was inexplicably canceled. At the time of the crash of TWA 514, exchanges between the FAA, USAF and airlines in regard to continuing confusion over correct approach altitudes was ongoing. Several airlines reported near misses over Mt. Weather (the terrain that TWA 514 hit) just before the time of the crash and advised the FAA, but the warnings were not passed along to pilots. (emphasis mine)

Retterer, R.C.. Error Chain: The Bitter End. Kindle Edition.

The next link, was the weather. A major snowstorm was moving through the midwest, approaching Indianapolis, the origin point of TWA 514, on Sunday, December 1, 1974. That Sunday in 1974 was the final day of the Thanksgiving holiday weekend.

The forecast for Columbus, an intermediate stop on Flight 514’s journey to Washington, D.C., was similar. The bottom line is that the weather forecast would have prompted everyone to be in a hurry to get out-of-town ASAP to beat the storm. In pilot talk, get-there-itis may have come into play. In any event, the plane would have had to be de-iced. That fact would also weigh on the pilots’ minds as they were always under pressure to be on time.

Destination Change

The flight from Indianapolis to Columbus was uneventful. TWA Flight 514 departed Columbus at 10:24 EST, 11 minutes late, with 85 passengers and 7 crew members aboard. The next link in the error chain happened about ten minutes after takeoff from Columbus.

From the NTSB (National Transportation Safety Board) Aircraft Accident report:

At 1036, the Cleveland Air Route Traffic Control Center (ARTCC) informed the crew of Flight 514 that no landings were being made at Washington National Airport because of high crosswinds, and that flights destined for that airport were either being held or being diverted to Dulles International Airport (IAD).

At 1038, the captain of Flight 514 communicated with the dispatcher in New York and advised him of the information he had received. The dispatcher, with the captain's concurrence, subsequently amended Flight 514's release to allow the flight to proceed to Dulles.

Neither the captain, the first officer or the flight engineer had landed at Dulles Airport before. TWA flew Boeing 707s, 747s and Lockheed 1011s into and out of IAD. These aircraft were largely used for trans-Atlantic, West Coast and other long-haul flights. Boeing 727s were normally the purview of DCA (Washington National Airport, not yet renamed for President Reagan). National’s main runway was too short to handle wide-body aircraft or Boeing 707s or Douglas DC-8s at that time.

Airborne and with only about a half-hour until scheduled touchdown, the pilots had to pull out their Jeppesen charts for Dulles International Airport (IAD) and brief for a landing at this alien airfield. All of that would have normally been done on the ground with much of the tedious details being handled by company dispatchers in New York. That added to the workload and put additional pressure on the pilots. Thus, the error chain lengthened. From the NTSB report:

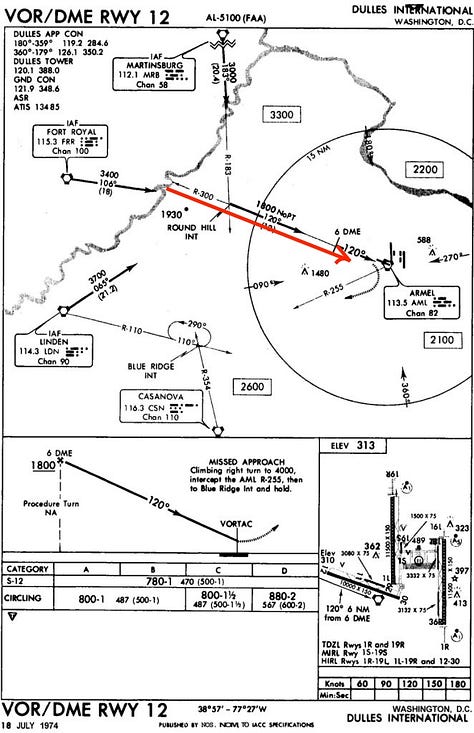

At 1042, Cleveland ARTCC (Air Route Traffic Control Center) cleared Flight 514 to Dulles Airport via the Front Royal VOR (Very High Frequency Omnidirectional Range Station), and to maintain flight level (FL) 290 (29,000 feet). At 1043, the controller cleared the flight to descend to FL 230 (23,000 feet) and to cross a point 40 miles west of Front Royal at that altitude. Control of the flight was then transferred to the Washington ARTCC and communications were established with that facility at 1048.

During the period between receipt of the amended flight release and the transfer of control to Washington ARTCC, the flight crew discussed the instrument approach to runway 12, the navigational aids, and the runways at Dulles, and the captain turned the controls over to the first officer.

Bitter End

Sailors call the last link in an anchor chain the bitter end. The bitter end of the Flight 514 error chain involved a misunderstanding of the Minimum Descent Altitude (MDA) for Flight 514’s approach to runway 12. MDA is the altitude below which an aircraft is not cleared to descend on a given flight segment. From my book:

Conversation in the cockpit was now a rapid-fire exchange of questions and comments. There was a debate over what their minimum altitude should be. The chart showed the minimum altitude at their next VOR, ROUND HILL, to be 3,400 feet. Customarily, however, if a controller cleared a flight for its initial approach, pilots could descend to the minimum approach altitude as shown on the approach plate. That approach altitude for Dulles was 1,800 feet, a difference of 1,600 feet.

At 11:04, Captain Brock reported to ATC (Air Traffic Control) that they were level at 7,000 feet. The controller then cleared them for a “VOR/DME approach to runway 12.” The captain read back the clearance.

As the flight descended through the clouds and light rain, turbulence increased and was commented on by the pilots. NTSB report:

At 1106:15, the first officer commented that, "I hate the altitude jumping around. Then he commented that the instrument panel was bouncing around….At 1106:27, the captain discussed the last reported ceiling and minimum descent altitude. (He) concluded, (We). . . “should break out.”

At 1106:42, the first officer said, "Gives you a headache after a while, watching this jumping around like that.” At 1107:27, he said, “you can feel that wind down here now….”

A few seconds later, the captain said, "You know, according to this dumb sheet it says thirty-four hundred to Round Hill…is our minimum altitude.”

The flight crew then debated whether they had to maintain 3,400 feet or whether they could descend to 1,800 feet, the published MDA for the approach to runway 12 at Dulles.

"When he clears you, that means you can go to your…” An unidentified voice said, "Initial approach,” and another unidentified voice said, "Yeah!" Then the captain said "Initial approach altitude.” The flight engineer then said, “We're out a…twenty-eight for eighteen.” An unidentified voice said, "Right,” and someone said, “One to go.”

Thus, the captain settled the debate based on the assumption that implicit in the controller’s instructions was that they were cleared to the initial approach altitude of 1800 feet. He ordered a descent to “Initial approach altitude.” At that point, they were at 2,800 feet as called out by the flight engineer with 1,000 feet to go to reach 1,800 feet. From the CVR transcript:

11:04 Capt: "Eighteen hundred [feet] is the bottom."

FO: "Start down. We're out here quite a ways. I better turn the heat down [probably referring to cabin heat]."

11:06:15 FO: "I hate the altitude jumping around." Then he commented that the instrument panel was bouncing around.

11:06:15 Capt: "We have a discrepancy in our VORs, a little but not much. Fly yours, not mine."

11:06:27 Capt discusses the last reported ceiling and minimum descent altitude and concluded: "...should break out."

11:06:42 FO: "Gives you a headache after awhile, watching this jumping around like that."

11:07:27 FO: "...you can feel that wind down here now."

Capt: "You know, according to this dumb sheet [referring to the instrument approach chart] it says thirty-four hundred to Round Hill—is our minimum altitude." The FE asked where the captain saw that, and the captain replied, "Well, here. Round Hill is eleven-and-a-half DME."

FO: "Well, but...."

Capt: "When he clears you, that means you can go to your...."

Unidentified: "Initial approach."

Unidentified: "Yeah."

Capt: "Initial approach altitude."

FE: "We're out of twenty-eight for eighteen."

Unidentified: "Right; one to go." [meaning 1,000 feet more before reaching the supposed level-off altitude of 1,800]

11:08:14 FE: "Dark in here."

FO: "And bumpy too."

11:08:25 Altitude alert horn sounds.

Capt: "I had ground contact a minute ago."

FO: "Yeah, I did too."

11:08:29 FO: "...power on this [expletive]."

Capt: "Yeah, you got a high sink rate."

FO: "Yeah."

Unidentified: "We're going uphill."

FE: "We're right there, we're on course."

Two voices: "Yeah."

Capt: "You ought to see ground outside in just a minute. Hang in there, boy."

FE: "We're getting seasick."

11:08:57 Altitude alert horn sounds.

FO: "Boy, it was—wanted to go right down through there, man."

Unidentified: "Yeah."

FO: "Must have had a [expletive] of a downdraft."

11:09:14 Radio altimeter warning horn sounds and stops.

FO: "Boy!"

11:09:20 Capt: "Get some power on."

Radio altimeter warning horn sounds again and stops.

At 11:09:22 TWA 514 struck the west slope of Mount Weather, about 25 nautical miles from Dulles at an elevation of about 1,670 feet.

NTSB Conclusion

In summary, this accident resulted from a combination of conditions which included a lack of understanding between the controller and the pilot as to which air traffic control criteria were being applied to the flight while it was operating in instrument meteorological conditions in the terminal area. Neither the pilot nor the controller understood what the other was thinking or planning when the approach clearance was issued. The captain did not react correctly to his own doubt about the line of action he had selected because he did not contact the controller for clarification. (emphasis mine) The action of the other air carrier pilot who questioned the clearance he received about 1/2 hour before the accident is the kind of reaction that should be expected of a pilot suddenly confronted with uncertainty about the altitude at which he should operate his aircraft.

Despite the chain of errors, oversights and acts of God that ultimately resulted in the fatal crash of TWA Flight 514, it really came down to that question that nagged me as I read through the details of the crash and was cited (above) in the NTSB conclusion. Given the confusion over their assigned altitude, why had the crew not called ATC for clarification?

As the report states, a previous flight of another airline on the same routing, its crew suffering from the same confusion over minimum descent altitude, called the controller for clarification and a crash was averted.

Probable Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of the accident was the crew's decision to descend to 1,800 feet before the aircraft had reached the approach segment where that minimum altitude applied. The crew's decision to descend was a result of inadequacies and lack of clarity in the air traffic control procedures which led to a misunderstanding on the part of the pilots and of the controllers regarding each other's responsibilities during operations in terminal areas under instrument meteorological conditions. Nevertheless, the examination of the plan view of the approach chart should have disclosed to the captain that a minimum altitude of 1,800 feet was not a safe altitude.

Flown West—RIP

Captain: Richard I. Brock, Los Angeles

First Officer: Lenard K. Kresheck, Los Angeles

Flight Engineer: Thomas C. Safrenek, Los Angeles

Flight Attendants:

Elizabeth Betsy Stout-Martin, 23, Lexington, KY

Joan E. Heady, 23, Olney, IL

Denise A. Stander, 21, Pittsburgh, PA

Jen A. Van Fossen, 22, Redding, CA

Late October three years ago, I lost one of my best friends in a Cessna during an ice storm in Lubbock, Texas. A blue norther was forecast to come through Texas as he flew from New Mexico. His Cessna had no deicing equipment, and he should have read the weather report and not have attempted to fly that afternoon. This was his key failure to follow procedure.

As he flew through the ice storm to try to land at the Lubbock airport, around three to five inches of ice accumulated on the plane’s wings and he crashed into a power line and the plane caught fire.

My friend was an ER doctor who was also into small-scale farming and large-scale gardening and chicken raising

I had a foreshadowing experience a couple of years before the accident where I saw that my friend was a bit more careless than I would have expected. We were learning to caponize cockerels, which is a surgical procedure that was frequently performed back in the early 1900s by chicken farmers who always had excess cockerels. This procedure has a somewhat steep learning curve, but I had guessed that a doctor would do well and would not be careless. He should have been slow at first but accurate.

Error Chain is a great book. I'm going to read it again.

Scott Randle