Winter Storm Watch

December 1, 2024 - Fifty years ago, today, I was sitting in the TWA flight attendant crew lounge at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport. A blizzard that had already devastated TWA’s home base of Kansas City (MCI) and points in between was moving east, currently unloading on Chicago. Eventually the storm would affect most of the eastern half of the country.

The lounge was packed, every available chair and BarkaLounger was spoken for. It was standing room only. I looked down through a concourse level window onto the TWA ramp that was empty of airplanes but blanketed by one to three feet of drifting snow. O’Hare was closed. Plows, back hoes and bulk haulers were losing the battle to clear runways, taxiways and ramp areas so that the airport could reopen.

All TWA flights in or out of O’Hare were canceled. In airline jargon, the stranded crew members’ status was tagged disposition pending. In other words, we were awaiting reassignment. Of course, company gossip and rumor mongering were dominating conversation. Chatter was interrupted when a male flight attendant walked into the lounge and shouted out, “Did you hear that we lost one. A 727 is down somewhere near D.C.” or words to that effect. It was news to us. He said he would go down to operations and pull up a crew list before they took the flight roster out of the computer.

We soon learned that the flight that went down was TWA Flight 514. The flight originated in Indianapolis and was bound for National Airport in Washington, D.C., with an intermediate stop at Port Columbus International Airport (CMH), now John Glenn Columbus International Airport. Shortly after takeoff from Columbus, the crew was advised that Washington National Airport was closed because of high crosswinds. After discussion with TWA dispatch, It was decided to divert the flight to Washington’s Dulles International Airport. Passengers would be bused to National.

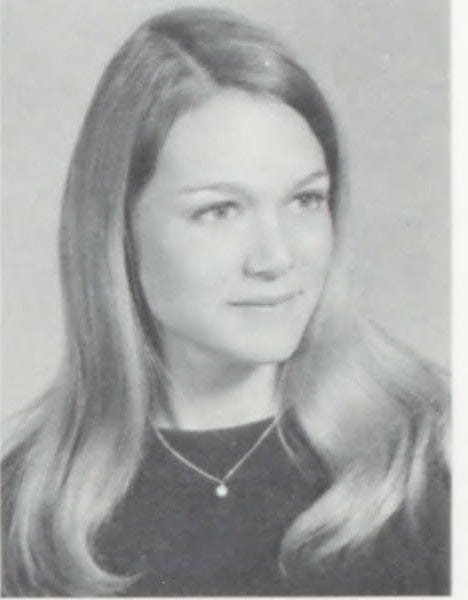

I was sitting with a group of F/As that I had known from training. When we first looked at the crew list, we did not recognize any names, pilots or flight attendants. One payroll number, however, was very close to ours, beginning with 39, followed by three digits. We knew that this person had to have been in our class, but no one recognized the name E. Martin.

Heavens to Betsy

Finally, someone made the connection that E. Martin, as the name was shown on the printout, was Elizabeth Betsy Stout-Martin, our classmate, whom we knew as Betsy Stout. This flight attendant recalled that Betsy had recently gotten married and had changed her name. At this point, we did not know how serious the crash was. We hoped and prayed that there were survivors and that Betsy was one of them. Soon enough, we learned the bitter truth. It was devastating news. No one survived. There was also a there but for the grace of God moment for me, and I’m sure for all of us.

I met Betsy at TWA’s Breech Training Academy in Overland Park, Kansas (suburb of Kansas City). We began flight attendant training together on April 11, 1973. The entire class numbered about 100, with 20 being males. It was only the second year that they had begun to hire male flight attendants, although TWA had always had male pursers and flight service managers, which I later became.

The group of 100 was divided into classes of about 20 each. Betsy and I were in the same small class. My most lasting memory of her is of a pretty, personable blonde, usually with her hair in a ponytail. Always smiling, she had a great sense of humor and healthy portion of Southern charm with a Southern lilt to her soft voice. She often wore University of Kentucky gear, frequently including a UK baseball cap with her ponytail sticking out the back. She had been a University of Kentucky student and had grown up in Lexington, Kentucky.

After a month of training, we graduated and officially went online on May 12, 1973. I was assigned to the New York International domicile (JFK-I). I believe Betsy first went to New York Domestic (JFK-D), although she later got her transfer to Kansas City where her fiancé had gotten a job.

A Happy Thanksgiving Turns Sad

As is the case in 2024, Thanksgiving of 1974 fell on Thursday, November 28th. Sunday, December 1, 1974, was the heavy travel day when most people who traveled for the holiday were returning home. For airline crews, any holiday meant a possible work day.

Crew schedules are determined by seniority. Pilots and flight attendants bid each month for published schedules, a line of time in airline jargon. When holidays come around, it is the senior flight attendants who are able to hold a line that has the holiday off. Thus, most of the crews flying that Sunday were junior. Many would have been called out on reserve (as was the case with the two most junior flight attendants on Flight 514 that day) because there are also an unusually large number of sick calls over the holidays.

Betsy was the most senior flight attendant on the crew. Second in seniority was Joan E. Heady who had gone online on July 20, 1973. The two most junior flight attendants, Denise A. Stander, 21, and Jen A. Fossen, 22, were new hires, having completed their training on November 7th of that year. Thus, as fickle fate had it, they had not even been flying for a full month before being killed in the crash.

Upon Further Review

In 1994, my wife and I moved to Fredericksburg, Virginia. She was a flight attendant for United Airlines and was based at Washington Dulles. I had taken early retirement from TWA in 1992 with the company in the midst of one of its several bankruptcies. In reading about the fatal crash of TWA Flight 800 on July 17, 1996, in which I lost more than a dozen former colleagues, I was reminded of the crash of TWA 514.

I realized that I really did not know many of the details of the crash. In those pre-Internet days, it was not easy to access NTSB (National Transportation Safety Board) accident reports. I finally found the report online, read it and everything else I could find on the crash, which surprisingly was not all that much.

The word at the time of the crash that I picked up from the company grapevine and some pilot friends, was that the crash happened near Frederick, Maryland, and that the Boeing 727 had come down on some secret government location that then had to be abandoned because the installation was not a secret anymore.

I was surprised to find that the crash had actually occurred in Upperville, Virginia, the aircraft the victim of CFIT, Controlled Flight Into Terrain. It had missed clearing Mount Weather by a few hundred feet. The crash location was only about 70 miles from our house. I made a pilgrimage to the crash site.

A Grave Visit

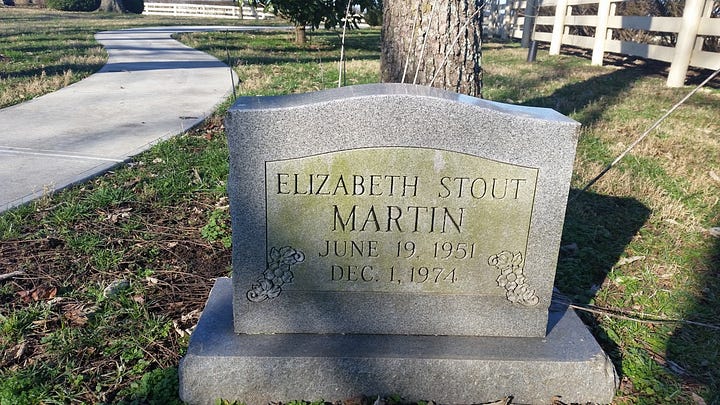

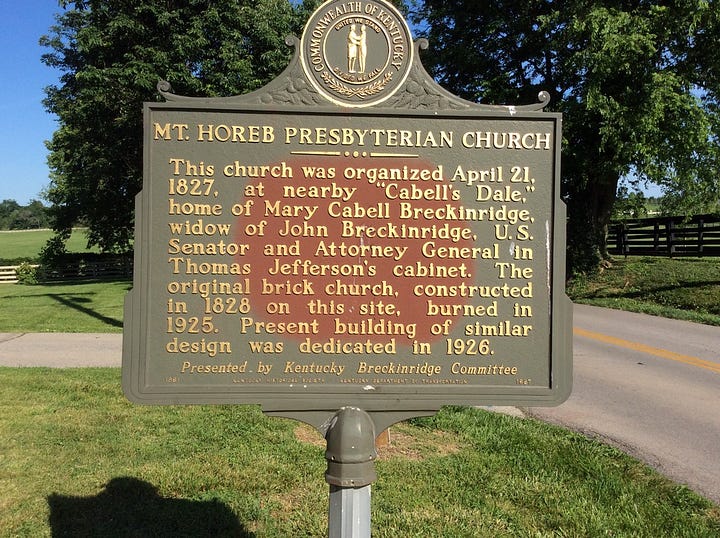

As I began researching the crash, I found Betsy’s grave site on Find-A-Grave—Mount Horeb Presbyterian Church outside of Lexington, Kentucky, where Betsy grew up. I eventually got in touch with the pastor. Coincidentally, she was a native of Fredericksburg, VA. To my surprise, she said she knew nothing about Betsy’s grave. She said that there was an old burial plot in the churchyard that had about five graves, including that of one of the church’s founders. The deceased were veterans of the Civil War and First World War. The last burial was in the early 20s. There had been none since.

Then I heard a woman in the background say that no, there had been the burial of the “girl who had been killed in the plane crash.” Betsy’s mother had known one of the longtime and well respected ministers. She asked him if Betsy could be buried in the churchyard, and he consented.

On a drive to my mother’s house in Arkansas, my wife and I stopped at the church. The church is surrounded by beautiful thoroughbred farms. It was hard to believe we were on the right track to find a church. But there it was. There was no one there when we arrived, so we poked around.

It was easy enough to find the old burial site and the old, worn tombstones that were barely legible because of erosion of the stone around the letters. Betsy’s grave was not among the original graves.

We finally found her gravesite off the side of a walkway that meandered through the beautiful gardens. It was just off a curving section of the path near the rear of the churchyard. Flowers were in bloom. Birds were singing. If one had to have a grave, this was about as nice a setting as one could hope for. On our first circuit of the garden, we missed the tombstone. One side of it was obscured by a tree and a large hosta. The gravestone, which looked brand new, was between two trees near the back white fence that separated the churchyard from the horse farm at its rear. We paid our respects and left.

In doing further research on the crash, I came upon the book The Sound of Impact, by Adam Shaw. That book got me interested in writing a book of my own based on the accident. There was some mention of the pilots in the book, but the book mainly concentrated on the passengers, including several VIPS who were onboard. There was nothing about the cabin crew, so I decided to write something from their point-of-view as I imagined it from my experiences.

Given the circumstances, the parts of the book dealing with the flight attendants and what they experienced had to be fiction. So, the technical details of the flight are taken from the NTSB report on the crash, while the fictional plot came from personal experience and experiences told to me by others.

Rarely is an airplane crash caused by a single catastrophic event. There are usually a series of mistakes, oversights or neglect that add up to disaster, like links in a chain. The crash of TWA Flight 514 was a classic error chain event. I will discuss the links in the error chain in part two.

I'm sorry you lost your friends Ross.